Inside the Motherboard: How System Architecture Shapes Electronic Performance

At the heart of every computing device lies the motherboard, a complex platform that orchestrates power distribution, signal routing, and component coordination—functions that are just as foundational to system stability as a current limiting resistor is to circuit protection. While processors and memory often dominate technical discussions, it is the motherboard that ultimately determines how efficiently and reliably these components work together.

The Motherboard as a System-Level Platform

Unlike individual electronic components, a motherboard must be designed as a complete system. It serves as the physical and electrical backbone that integrates processing, memory, storage, power, and communication into a unified whole.

From an engineering standpoint, the motherboard:

- Defines electrical interfaces between subsystems

- Controls power flow and grounding strategy

- Establishes signal timing relationships

- Sets mechanical and thermal constraints

Every design decision on the motherboard has ripple effects across the entire product.

Architectural Role of the Motherboard

A motherboard is not just a carrier for components—it enforces the system architecture.

Data Flow Coordination

High-speed data paths such as:

- CPU to memory

- CPU to chipset

- PCIe lanes to expansion devices

must be carefully routed to maintain synchronization. The motherboard determines bus topology, lane allocation, and bandwidth priorities.

Power Architecture Integration

Modern systems require multiple voltage domains, often with dynamic load changes. The motherboard integrates:

- Power input stages

- DC-DC conversion circuits

- Decoupling and bulk capacitance

A robust power architecture ensures stable operation during peak processing loads and transient conditions.

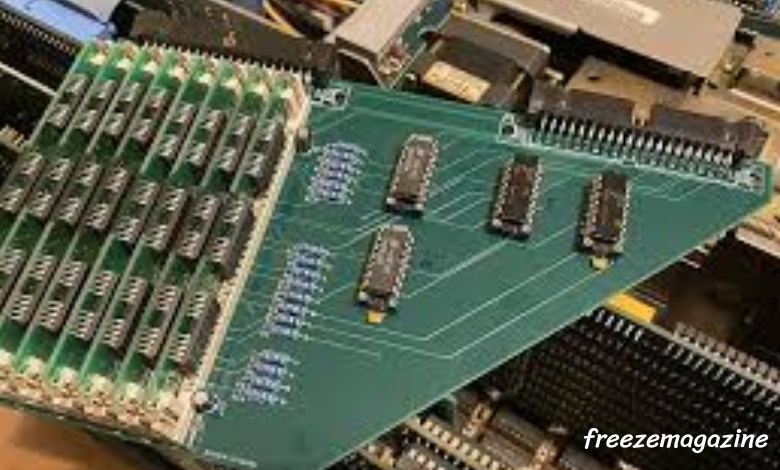

Component Placement and Its Impact

Component placement on a motherboard is never arbitrary. Layout decisions directly affect signal quality, thermal behavior, and manufacturability.

Proximity Matters

Key placement principles include:

- Keeping memory close to the CPU to reduce latency

- Placing VRMs near high-current loads

- Separating noisy digital circuits from sensitive analog areas

Improper placement can increase noise, heat concentration, or signal distortion.

Mechanical Constraints

Motherboards must also conform to:

- Form factor standards (ATX, Micro-ATX, ITX, custom industrial sizes)

- Connector alignment with enclosures

- Structural rigidity requirements

These constraints often compete with optimal electrical layouts, requiring careful trade-offs.

Multi-Layer PCB Design in Motherboards

Most modern motherboards rely on complex multi-layer PCB stack-ups to handle dense routing and strict electrical requirements.

Typical Layer Functions

- Outer layers: high-speed signal routing and component mounting

- Inner layers: solid ground and power planes

- Additional signal layers: controlled impedance routing

More layers allow better isolation and cleaner return paths but increase fabrication cost and complexity.

Signal Integrity as a Design Driver

As interface speeds increase, motherboard design is increasingly driven by signal integrity rather than schematic logic.

Common Challenges

- Impedance discontinuities

- Electromagnetic interference (EMI)

- Timing skew in parallel buses

Designers rely on controlled trace geometry, reference planes, and simulation tools to predict and mitigate these issues before production.

Thermal Design at the Board Level

Thermal management is not limited to heatsinks and fans—the motherboard itself plays a role in heat distribution.

Board-Level Thermal Strategies

- Thick copper layers to spread heat

- Thermal vias under power components

- Strategic airflow channeling through layout

Poor thermal design at the motherboard level can reduce component lifespan even if individual parts are rated correctly.

Expandability and Interface Design

The motherboard defines how a system evolves over time.

Common interfaces include:

- PCIe slots for expansion cards

- M.2 connectors for storage and wireless modules

- Headers for I/O, sensors, and control signals

Designing these interfaces requires balancing future-proofing with space and cost limitations.

Manufacturing Challenges Unique to Motherboards

Motherboards are among the most challenging PCBs to manufacture due to:

- High component density

- Fine-pitch packages and BGAs

- Mixed assembly processes (SMT + selective soldering)

Process consistency is critical, as even small deviations can cause intermittent failures that are difficult to trace.

Inspection and Validation

Given their complexity, motherboards undergo extensive quality control, including:

- Solder paste inspection (SPI)

- Automated optical inspection (AOI)

- X-ray inspection for hidden solder joints

- Functional and stress testing

These steps ensure that the motherboard performs reliably across real-world operating conditions.

Why the Motherboard Defines the User Experience

End users may judge a product by speed or features, but many real-world issues—random crashes, poor upgrade compatibility, thermal throttling—can often be traced back to motherboard design.

A well-designed motherboard delivers:

- Stable performance under load

- Long-term reliability

- Predictable upgrade paths

- Consistent electrical behavior

In contrast, design shortcuts at the motherboard level often surface as field failures months or years later.

Conclusion

The motherboard is the silent architect of system performance. It shapes power integrity, signal quality, thermal behavior, and expandability long before software ever runs. By viewing the motherboard as a system-level platform rather than a passive PCB, engineers and manufacturers can build products that are not only functional, but robust, scalable, and dependable over their entire lifecycle.

Post Comment